| |

|

|

Absorption

+ Transmission

Published by the National Academy of Sciences

Introduction by JD Talasek, Director of Exhibitions

and Cultural Programs, National Academy of Sciences.

Essay by Andrew Solomon, author of The Irony Tower: Soviet

Artists in a Time of Glasnost and the bestselling novel A Stone

Boat. He is a fellow of Berkeley College at Yale University and

a member of the New York Institute for the Humanities. |

Time

lapse in vivo images collected over 24 hours of a neuron in the

brain of a tadpole. Courtesy Dr. Kurt Haas and Dr. Hollis Cline

at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory.

|

Providing

a point of reference that embodies both literal and symbolic meaning,

Mike and Doug Starn utilize the theme of light as a central component

in their work. Light, an inherent element in both vision and photography,

is a simple yet powerful vector of life, knowledge and enlightenment.

The Starns’ researches have spurred interconnected bodies

of artworks that combine seemingly classical images of trees and

leaves, branch-like angiograms, and other complex patterns that

allude to the cardiovascular system and the neuronal structure of

the brain.

In these interpretations of flora, trees—dependent on photosynthesis

and its carbon deposits—become the calligraphy of the sun and

are a point of entry into the body of work called Absorption

of Light, the Starns’ territory of philosophical investigations.

A photograph is vision and thought written by light in its opposite.

Paradoxically, black is not a void of light; black is filled with

light, black is a reservoir of light: in the Starns’ conception,

black illuminates.

Through their innovative and conceptual layering of images of natural

phenomena with those made by the most advanced scientific and medical

technology, the artists establish a unique lexicon of visual metaphors.

The Starns have drawn on a variety of techniques from the history

of photography and the current digital age to create this body of

work. By mingling the antique with the contemporary, both in subject

matter and materials, the artworks are a reflection of veins flowing

between many branches of knowledge.

“We cannot understand the forces which are effective in the

visual production of today if we do not have a look at other fields

of modern life.”

This statement, made by the German art historian Alexander Dorner

in the early part of the twentieth century, resonates in the work

of Doug and Mike Starn. Perhaps, because they are identical twins,

their existence is already a coincidence of nature decodable by

science, and their art is intuitively interdisciplinary. Art and

science merge when a gnarled black branch reaches for the light

and our thoughts stretch to follow its lead, or the initial visual

impact of a leaf magnified for inspection dissolves into delicacy:

The Starns link the evident and the ephemeral. Their process is

based on the idea that visual art exists as a laboratory for knowledge,

both physical and philosophical. Their work serves as both a record

of observation and a portal for contemplation.

—JD Talasek

|

“From

Imaging to Image”

For many years, advancement in biological psychiatry involved innovations

in molecular biochemistry and biophysics. We learned which substances

potentiated which cellular events, and mapped unfathomably complex

chains of reaction. We began to understand transporter theory and

to trace episodes so quick that they seemed to defy our notions

about time. We digitized consciousness into neural components, and

specified the electrical impulses and chemical interactions involved

in every process from aggression to love to the formation of memories.

On the basis of these insights, new compounds were designed to treat

a variety of previously intractable mental and neurological illnesses.

Their novel mechanisms of action were somewhat meanly represented

by formulae and theories and abbreviations and equations. What we

understood surpassed our abilities of description.

In the past decade, that has changed. Many of the most important

developments in brain science have been in imaging. With the emergence

of MRI and other advanced technologies, we have begun to chart what

is happening deep and fast, things we couldn’t see with any

previous methods, and this visual capacity is allowing us a fluid

mastery previously inconceivable. The word “imaging”

suggests photography, but in fact what an imaging mechanism provides

is a great accrual of numbers, which computers put together to make

visual symbols of neural activity. The image is the humanization

of information too vast to absorb otherwise: if a picture is worth

a thousand words, it is worth a hundred thousand numbers. With imaging,

what was abstract becomes palpable; what we comprehend visually

is more convincing to us than numeric sequences. Suddenly, we are

looking into the brain itself while it is alive and active. Jules

Verne never proposed anything more thrilling and unlikely. We can

take someone’s consciousness, previously a philosophical problem,

and describe what it looks like; we can subtype illnesses because

we can see the difference between one and the next before we even

begin noting symptoms. Our wildest explorations of outer space have

never brought us more startling, informative, weird pictures than

these graphic translations of magnetism and mathematics.

Doug and Mike Starn have always made work that looks deep inside

their subjects and addresses the status of the image both as representation

of fact and as fact itself. Their photographs are not shorthand

for numbers, but they are just as full of information as brain scans,

vivid and explicit manifestations of the intersections between reality

and ideas. Their early distressed images reflect the transience

of photographic truth, which documents a reality already long gone

when a print is made. This material contemplates the history of

the image as well as of the subject. In more recent pictures, they

have explicitly studied light, the medium and message of all photography.

In some pieces (“Attracted to Light”), they examine

the interaction between light and desire: moths flit towards a glow,

their powdery wings refracting the brightness for the sake of which

they so often give their lives.

The Starns’ newest body of work (“Structure of Thought”)

uses trees to express the relationship between the light that makes

photographic prints and the translation of that light into life

through the process of photosynthesis. In some sense, the tree is

light made flesh, much as the brain scan is math made image. The

physical resemblance between these depictions of trees and leaves

and portrayals of the seemingly infinite branching of dendrites

is striking, but the deeper parallel lies in the fact, rather than

the appearance, of a functional complexity. The tree photos are

not x-rays; what they show is out there to be seen by anyone. Yet

they take on a diagrammatic quality and seem to elucidate the structural

architecture of plants. They remind us how natural order often looks,

at first glance, like chaos.

The essence of the trees is a system of distribution, in which the

massive trunk relies on the branches, which in turn depend on leaves;

there is a symbiosis between the singular and the multiple. This

process is akin in some ways to the process of cell division on

which life is predicated, and, equally, to the relationship between

a photographic negative and the many generations of prints that

can be made from it. As we look at the Starns’ trees, we recognize

how the strength of the core relies on the constant fine division

of the component parts. The leaf series (“Black Pulse”)

is a logical extension of the tree series: the multitudinous veins

of the leaf are yet further refinements of the capillaries represented

by the Rapunzel cascade of the branches. The series limns the innumerable

divisions by which living things survive, demonstrating how the

endless branching that we can see becomes an endless branching of

what we cannot. It is as though this were a family tree, the trunk

a great patriarch, the branches sons and daughters, the leaves all

full of cousins.

|

|

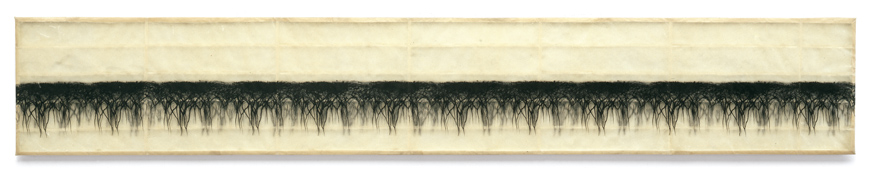

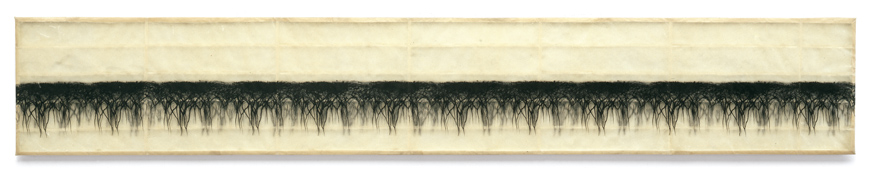

Structure of Thought 16 (preparatory

composition),

21 3/4 x 133 1/2 in., 2005. This piece is derived from an image of

many cerebal neurons expressed with yellow fluorescent protein.

Courtesy Dr. Karel Svoboda, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory.

These images resemble,

also, the decision trees of game theory. Every possible choice has

a variety of consequences, and every one of those has a variety

of further sequellae, and so our minds from a single simple question

develop an unfathomable variety of ideas; multiplicity is the shape

of consciousness. Every thought generates myriad potentials, and

intelligence relies on the capacity to keep all these overlapping

and sometimes contradictory implications simultaneously active.

If you can see the mass of the trunk and the veins of the leaves,

you can achieve mental and psychological sophistication: you can

contemplate outcomes and make what we call informed decisions. You

can become wise. These photographs translate wisdom into a visual

iconography.

What should not go unnoticed in all these profound studies is beauty.

We love both order and complexity, and the Starns are able to achieve

a high level of both. Crowded as Brueghel, strange as Bosch, symmetrical

as Leonardo, and rich as Rembrandt, these images are endlessly satisfying.

Trees are lovely anyway, but here the artists have distilled that

loveliness. These are not only splendid forests, but also magnificent

photographs of the very structures of life.

—Andrew Solomon

|

|

|