Descartes claimed that the blind see with their hands; it is a positivist view that to touch something, to determine its contours, is to know it: I “see” it, therefore it is. But this idea does not so much redress but renew the gulf between seeing and knowing: the classic mind-body problem. Centuries later, the French phenomenologist philosopher Maurice Merleau-Ponty refocused Descartes’ analysis. “There is no vision without thought,” he wrote. “But it is not enough to think in order to see.” In other words, our bodies—our vision—are the permanent condition of our experience, and thought is born by what happens in and on the body. We are conductors; absorbers and emitters of the universe’s energy.

A leaf falls from a tree. A flash of light crosses a shadowed statue. A snowflake dissolves in the air. And in a darkened exhibition hall, an icy blue radiance sizzles and flashes.

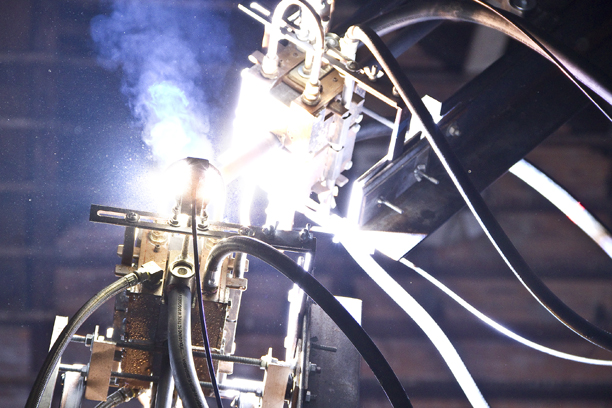

In their most ambitious project to date, Mike and Doug Starn present Gravity of Light, as much a system of transmissions as an exhibition of objects for contemplation. Part sculpture, part scientific experiment, the peculiar thirteen-foot-tall mechanical structure at its center is titled Leonardo’s St. John or This is my Middle Finger (2005). In the painting by da Vinci (himself an artist-inventor and maker of meaning), John the Baptist points his finger to the heavens, indicating the path to enlightenment. In the Starns’ carbon arc lamp—an adaptation of an 1804 model by British physicist Humphry Davy—electrifies that light with carbon-rod “fingers” that conduct a current between their respective nodes, producing a brilliant point of light too dazzling for the naked eye. Taped like a notice to the lamp’s stem is a copy of the Leonardo painting. However, in the Starns’ version, St. John’s gesture of benediction has been digitally replaced by one of profanity. As Martin Barnes, senior curator of photographs at London’s Victoria & Albert Museum, writes, this gesture “is like a rebuff, aimed at paltry human confidence in the face of eternity. Pure light is the carrier of this awesome power, at once the message and the messenger. And the news is this: light can bring, in equal measure, life and destruction, energy and fear, illumination and obscurity.”

Since well before the Renaissance, light has been used for and understood as a metaphor for illumination, spiritual or intellectual; light is the opposite of dark. Merleau-Ponty writes that our understanding of an event is constituted not only by experience but also by its opposite—we know a contour by its line as well as the spaces it limns on either side:

“Between the seeing and the seen, between touching and touched, between one eye and the other, between hand and hand, a blending of some sort takes place—when the spark is lit between sensing and sensible, lighting the fire that will not stop burning until some accident of the body will undo what no accident would have sufficed to do.” (Eye and Mind, 1964)

Our knowledge is a Möbius strip, constantly constituting and constituted by the world our bodies find themselves in. And what we think of as our “self” is therefore not a fixed point in space, but the location of a dynamic flow of relationships between opposites. The Starns’ carbon arc lamp electrifies (literally) this notion:

”Light is thought, light has gravity, light is what attracts us. The sun is what we want, who we want to be, who controls us. It is the future and the past. A Light too bright to look at, although light itself is invisible. The collection of light is black, and contradictorily, black is the absence of light. Black is both the void and the reservoir of what we need.” — M+D Starn

In Gravity of Light, the Starns’ lamp, like the sun, provides a gravitational center to their universe. They choose the language of photography, writing in light. Their cameras are tools to mediate between sense and sensed, to introduce light into darkness. Light, therefore, is the medium and the message.

The lamp casts light on seven of their elemental photographs, all of which have harnessed the power of light in ways both literal and poetic. These monumentally scaled photographs become chapels in an industrial cathedral. Their subjects are both emblems of and witnesses to the dualistic character of light, with its power to give life and to destroy it, to illuminate and to blind. The ill-fated moths of the Attracted to Light series are caught moments before self-immolation, drawn to the light that kills them, their images pinned, momentarily, on photographic paper. Across the gallery, abstracted growths that could be trees—or a neural cell’s dendrites—take root in the Structure of Thought series. The gnarled branches are, in effect, the sun’s signature. The leaf, the fruit of the branch, falls away in Black Pulse and Black Pulse Lambda. These desiccated leaves, recorded in filigreed detail, signal both decay and renewal; ashes to ashes, dust to dust. Lastly, there is the towering image of a Bodhisattva, the eighth-century Buddhist monk Ganjin, who, though blind, found illumination within.

Taken together, Gravity of Light represents a remarkable body of work in which all parts depend on the whole, representing not a flattening of difference but a deepening. Opposites like black and white, light and dark, art and science, the eternal and the ephemeral are revealed not only as false dichotomies, but as necessarily dialectical relationships—each casts new light upon the other. Merleau-Ponty characterizes this as akin to one’s left hand shaking one’s right. But as the fleeting light of the lamp makes clear, our grip on reality is only as strong as the one hand shaking the other. The flesh feels only as solid as the answering pressure.

With Gravity of Light, the Starns upend the trees, plumb a reservoir in a void, point a middle finger to the heavens, and expose the flesh of contingency. The Starns’ art does not hold the world in suspension as an object for contemplation, but rather suspends the viewer in the world.

Gravity of Light was originally presented at Färgfabriken Kunsthalle, Stockholm, in December 2005 and is scheduled to travel to the Detroit Institute of Arts in 2009. The rest of the domestic and international tour is currently in development.

Reviews

POST Gazette 12/31/ 2008

Pittsburgh City Paper 10/23/ 2008

POST Gazette 10/22/ 2008

Pittsburgh Tribune-Review 10/16//2008

Pitts Post-Gazette 10/ 09/ 2008

Pittsburgh PBS program "On Q Magazine" (Requires Windows Media Player)

The San Francisco Chronicle, by Kenneth Baker 11/21/08

__________________________________________________________________________________

Färgfabriken Kunsthalle Stockholm Sweden, January 2005

Reviews

ARTFORUM by Tom Vanderbilt

Svenska Dagbladet (in

Swedish)

Dagens

Industri (in Swedish)

Disajn

(in Swedish)

Stockholm (in

Swedish)

|